The Hidden Struggles of My First Doctoral Paper

My very first paper, Automated Audio Captioning using Transfer Learning and Reconstruction Latent Space Similarity Regularization, was published at ICASSP 2022 during my doctorate. At the time, I was idealistic and optimistic about many research directions; I wanted to publish something novel and exciting. Now, looking back, what stands out more are the struggles, the wrong turns, and how my thinking evolved.

Fun Fact! Because of Covid, ICASSP2022 was held online on gather.town, making my very first research show and tell a virtual presentation.

This post is not a rehash of the paper. It is about how I approached the problem, my struggles at the time, and what I learned from the process.

Background #

Three years ago, right after I passed my doctoral Qualifying Exam in 2022, Natural Language Processing was all the rage. It felt like every other week there was a new model to beat. During the first two years of my doctorate (2020–2022), I worked on non-autoregressive text-to-text models but found myself increasingly constrained by the GPU VRAM limits in my lab. It didn’t help that our GPUs were shared with the entire university; competition was so stiff that I often had to wake up in the middle of the night just to find an available slot.

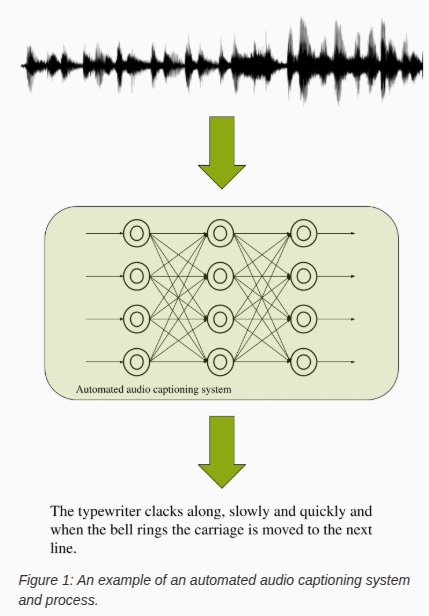

At that time, my advisor was working in Audio Processing; a field which, at the time, had mostly yet to catch up with the impressive progress of its sister fields. He introduced me to Automated Audio Captioning, a relatively new task that had been introduced in the DCASE challenge.

Audio captioning appealed to me because it sat at the intersection of multiple domains: audio signal processing, representation learning, and text generation. Compared to speech recognition, it felt less “solved” and more open-ended. The model wasn’t just mapping sound to words; it was trying to describe a scene. Furthermore, as a hearing-impaired individual, focusing on this research felt personal and meaningful.

Transfer learning had just become the de facto method for training models. Every month, larger foundation models were released. In vision and NLP, pretrained models were already standard, but in audio, the field still felt underexplored. I wanted to see how far we could go by reusing strong audio representations instead of learning everything from scratch.

Early Assumptions and How They Changed #

Initially, I assumed the main challenge would be model architecture design: choosing the right encoder–decoder setup or deciding between CNNs and Transformers. I thought if we picked a good structure, the rest would follow.

What I underestimated was:

- How ambiguous the captions and audio could be, even to the human ear.

- How sensitive training was to small design choices,

- How much time would be spent simply waiting for experiments to complete.

Very quickly, progress became less about “big ideas” and more about careful iteration.

The Core Idea, in Simple Terms #

At the time, there were two lines of research that I believed had potential: Adapter layers and more meaningful loss functions. With these in mind, I tried reframing the task as maximizing the similarity between intermediate text and audio embeddings using a small set of parameters. Additionally, because I was severely constrained by compute, I decided my research would have a “low-compute” angle.

The paper ended up with two main components:

- Transfer learning from pretrained audio models to get better acoustic features.

- Reconstruction Latent Space Similarity Regularization (RLSSR), a small set of layers that encouraged consistency in the latent space when reconstructing audio features, with the aim of guiding the model toward more meaningful representations.

At a high level, my thinking was: If the model is forced to keep its internal representations aligned and structured, it might generalize better, especially with limited data.

On paper, this sounds straightforward. In practice, it meant a lot of parameter grid search:

- how strong the regularization should be,

- where in the network to apply it,

- and how to balance it against the captioning loss.

Most of this was decided empirically. Sometimes, changing a particular hyperparameter would improve results across a few experiments, only for that improvement to disappear when something else changed. It felt like hitting a jackpot; you had to stumble upon the exact right combination to get consistent results.

What Was Actually Hard #

Knowing what to trust

Metrics like BLEU, METEOR, CIDEr would increase, but qualitative outputs did not always look clearly better. I often found myself manually reading captions and wondering whether the improvement was real or just metric noise. Should I posit that these metrics from machine translation are unsuitable? Would anyone even take me seriously?Debugging representation learning

When things did not work, it was hard to tell why. Was it the encoder? The decoder? The regularization? The data? This forced me to develop a more systematic habit of ablations, even when compute was limited.

What Still Feels Valuable #

Despite all that, I still think the research from this paper taught me a lot, considering I was fresh in Audio Processing: how to integrate pretrained components into a new pipeline,

- how to reason about latent representations,

- and how to turn a vague intuition into something testable.

- how to iterate faster and not be too fixated on an idea that might not work out.

More importantly, it shaped how I now think about ML systems: not just as architectures, but as a intricate system of moving parts.

Closing #

This paper represents a snapshot of how I thought and felt about machine learning at that time. A frenzy of experimentations. A constant worry that my results would get superseded the very next week. Looking back, I am proud of the outcome and what i managed to achieve given my limited resources. Though I would have probably not given it a name as obscure as RLSSR.

Up Next: Reflections from my next paper.