What my Second PhD Paper Taught Me

Paper. If you haven’t read my reflections about my first paper, click here. Lots of lore in there.

Mindset Check #

I had just come off publishing my first paper and wanted to ride that momentum into another one. At the same time, I could feel the so-called “AI wars” accelerating. Every other week, OpenAI or Meta seemed to be releasing a larger model or a more impressive result. I was very aware of the clock ticking on my PhD, and I was in a hurry to graduate.

Mentally, I was anxious. Not about the work itself, but about relevance. I was worried about being left behind while industry labs pushed out bigger and bigger models at a pace academia simply couldn’t match.

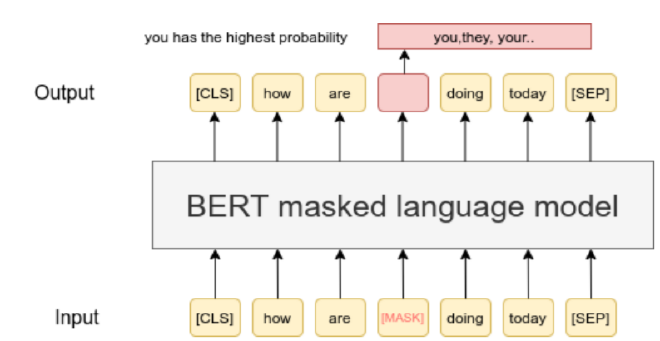

This paper came from a mix of excitement and pressure. Pretraining tasks were all the rage back then. Masked language modelling, next sentence prediction (BERT), and similar objectives seems to be the trend. To me, many of these felt almost like primary school homework exercises. Useful, yes, but still largely classification tasks. I was more interested in whether these simple ideas could be adapted to open-ended sequence generation.

Then OpenAI released a paper on chaining non-trivial reasoning steps for math. That was the spark. The idea that how you present data during training could matter just as much as the architecture itself stuck with me, and that became the seed for this paper. Chain of thought reasoning, as of writing, became the de facto standard for eliciting complex reasoning from large language models.

Initial Expectations #

Coming off my first published papers alongside many failed experiments before this research project, I did not expect smooth sailing. That said, I already had a working data-to-results pipeline, which meant I could implement my intended strategy relatively quickly. This alone made the project feel unusually frictionless in the early stages.

This time, I wanted my research angle to focus on a training method rather than overthinking model design. The goal was to make it as model-agnostic as possible. In theory, this could be plugged into many different setups.

The inspiration itself was simple, maybe even a bit naïve. If children are unable to form proper sentences with correct grammar before a certain age (at the risk of anthropomorphizing models), perhaps our models might also learn better if they started small.

Based on that intuition, I designed a curriculum where keywords from each caption were fed in as ground truth at the beginning of training. As training progressed, the model would slowly transition back to the full ground truth captions. In my head, this also acted a bit like dropout; a form of regularization that nudged the model away from over-reliance on exact sequences.

Constraints I Couldn’t Ignore #

There were quite a few experiments I wanted to include in the paper but had to remove due to space constraints. I had actually run several different curricula as ablations, exploring variations beyond what eventually made it into the final version.

In the end, I narrowed it down to two: a keyword curriculum and a frequency-based curriculum, with the latter serving as a contrast. The goal was not to exhaustively explore every possible curriculum design, but to support the hypothesis that keyword-based progression was particularly useful for automated audio captioning.

In hindsight, many of these decisions were shaped less by theory and more by practicality. Time, space, and compute all played a role in determining what survived into the final paper.

Looking Back With More Experience #

Looking back now, this paper actually felt like a breeze compared to the hurdles I faced in later work. That alone probably explains why it remains one of my favorites.

If I were to redo it today, I would definitely adopt a more rigorous experimental methodology. At the time, finding the right experimental settings often felt like searching for a needle in a haystack—blindfolded. But I also recognize that I would not have learned this lesson without going through that phase.

I published this paper in APSIPA2023. This was my first conference post lockdown (or “circuit breaker” as coined in Singapore) and I got to travel to Hanoi, Vietnam! I also helped to present a paper for another paper I helped author. Presenting in real life was a totally different experience. I couldn’t rely on live captions to aid my hearing impairment, only my wits. Still, it was fun.

Given where I was in my PhD and what I knew then, most of the decisions I made were reasonable. The paper’s relative simplicity, and the fact that it came together more smoothly than others, makes it stand out in my memory. Not because it was the most sophisticated work I did, but because it taught me how research can sometimes flow, and how rare that feeling actually is.